The Fed is Talking About Negative Rates Again

After picking Notre Dame to upset Clemson, then Bama to beat Clemson, then the Rams to beat the Pats, I’ve gotten a lot of emails lately to the effect of “I hope you know interest rates better than you know football…”.

Unfortunately, I don’t. So take the following newsletter on negative interest rates with a grain of salt.

Last Week This Morning

- 10 Year Treasury back down to 2.634%, near to that 2.62%-ish support level

- German bund down to 0.08%, the lowest since October 2016

- Japan 10yr is negative again, yielding -0.03%

- 2 Year Treasury down to 2.47%

- LIBOR at 2.51% and SOFR at 2.38%

- $8.9T in global sovereign debt has negative yields

- Small Business Confidence has fallen back to pre-election levels, with only 14% of small business owners expecting the economy to improve this year vs 36% that expect it to weaken

- The concisely named “Global Economic Policy Uncertainty Index” has hit an all-time high

- Janet Yellen said it’s entirely possible that the next Fed move is a cut, not a hike

- EU lowered GDP and inflation forecasts for the eurozone by more than 0.5%

Negative Interest Rates

The San Francisco Fed made some headlines this week with a research paper entitled, “How Much Could Negative Rates Have Helped the Recover?” This paper, authored by Dr. Vasco Curdia, examined whether the Fed should have taken rates negative following the crisis. It sounds crazy on the surface of it, but Dr. Curdia earned his PhD in Economics from Princeton, making him far smarter than me and almost as smart as you.

I will attempt so summarize his takeaways in this newsletter, but here’s the full article if you are so inclined: (here’s a link to the full paper if you are so inclined: https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2019/february/how-much-could-negative-rates-have-helped-recovery/)

Once the Fed had cuts rates to 0% in December 2008, it had to turn to unconventional monetary policy tools like Quantitative Easing and forward guidance to help spur growth. But other countries like Switzerland, Sweden, and Japan experimented with negative interest rates.

Bernanke himself is on record as having said negative rates have not created issues that some feared. In an publication three years ago, he noted, “The idea of negative interest rates strike many people as odd. Economists are less put off by it, perhaps because they are used to dealing with ‘real’ (or inflation adjusted) interest rates, which are often negative.” In other words, while most of us frequently look at the headline interest rate, economists more commonly factor in inflation. If inflation is greater than the nominal rate of interest, we have negative ‘real’ rates. This isn’t uncomfortable territory for economists.

Bernanke added, “The anxiety about negative interest rates…seem to me to be overdone. Logically, when short-term rates have been cut to zero, modestly negative rates seem a natural continuation; there is no clear discontinuity in the economic and financial effects of, say, 0.1% and -0.1%. Moreover, a negative interest rate on bank reserves does not imply that the most economically relevant rates, like mortgage rates or corporate borrowing rates, would be negative.”

The San Francisco Fed paper last week argues implicitly for the elimination of 0% as the lower bound. The negative rate experiment in Switzerland pushed rates to -0.75% yet cash balances in banks did not plunge. While it may seem counterintuitive to pay someone to hold your money, you can’t just take a few billion here and there and stuff it under your mattress at home.

Just as importantly, there have been no serious negative side effects on financial stability in countries that have used negative rates. This is one of the critical reasons the Fed seems willing to dip its toes into negative territory.

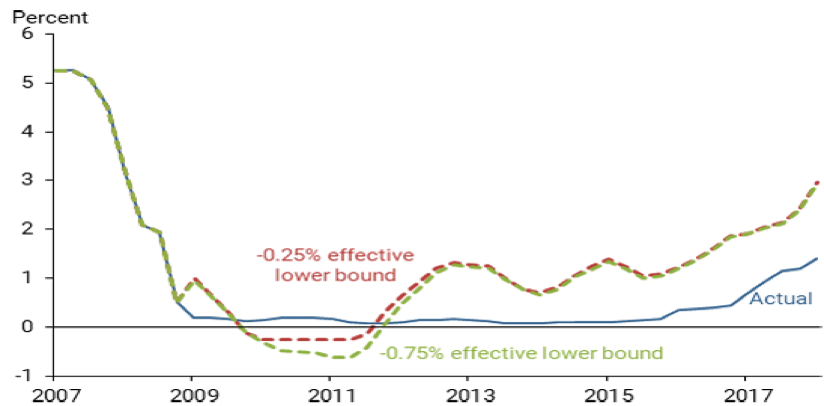

Curdia ran hypothetical scenarios where Fed Funds was lowered to -0.25% and -0.75% in 2010 and 2011. His model suggests that Fed Funds would have rebounded more sharply after this than what we actually experienced by stopping at 0%.

In this graph, the blue line is the actual Fed Funds, while the dashed red and green lines illustrate the path of Fed Funds had we dipped into negative territory. Notice how much more quickly his model suggests Fed Funds would have rebounded and that it would have reached 3.00%.

Again – the more sharply the Fed intervenes, the more quickly the market can rebound.

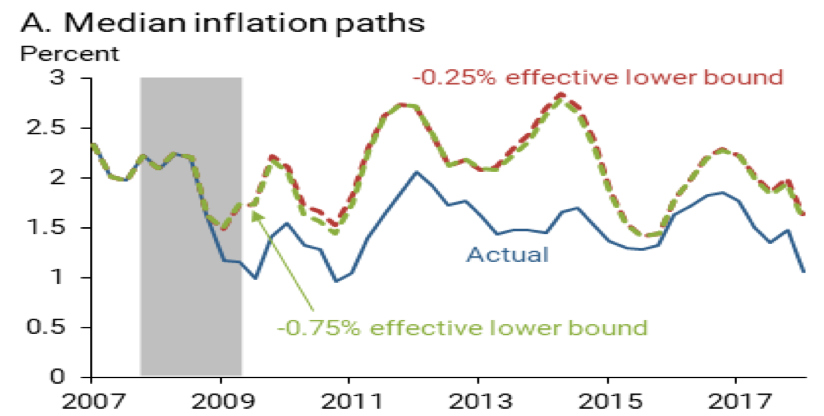

He also measured the impact these hypothetical monetary policy actions would have had on inflation. Guess what? Inflation would have also rebounded much more quickly.

Curdia’s conclusion was that negative interest rates would have helped turn the economy around more quickly without severe negative consequences. He does caution that rates more negative than 0.75% could have unforeseen risks and that the sample size is relatively small.

“These estimates are subject to substantial uncertainty. Nevertheless, it is likely that a negative lower bound would have reduced the depth of the economic contraction and further reduced downside risk.”

Why Now?

Even if the Fed has no intention of experimenting with negative rates right now, Curdia’s paper serves as a form of forward guidance.

If the Fed is done hiking, the market may be concerned it doesn’t have enough ammo to cut rates enough to stave off a recession. In previous downturns, the Fed frequently has cut rates by as much as 3.00% – 5.00%.

Since the Fed was unable to get rates above 3.00%, cutting by 3.00% isn’t an option…if you believe the floor is 0%.

So the Fed is setting out to change market perception. Maybe the floor isn’t 0%, it’s really -0.75%. That’s an additional 3 rate cuts. That’s more ammo. Convince the market that the floor isn’t 0% – it’s negative. We have more room than you are giving us credit for!

The Fed is talking about negative rates now to convince the market it has more ammo if needed.

Global Negative Yields

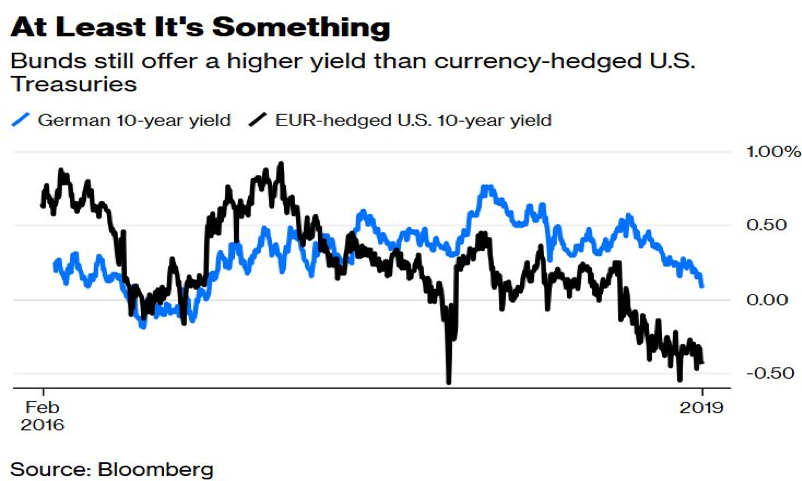

Global negatively yielding sovereign debt is back up to nearly $9T. Nearly 40% of all eurozone government bonds have a negative yield currently, a nine-month high. The German bund appears poised for negative territory again. On Friday, it closed at just 0.08%. Makes our 10T look like a great alternative, right?

But for a European firm, it isn’t as simple as buying the US 10 Year Treasury instead because they have to factor in the cost of different currencies. Once that is factored in, the US 10T yield is about -0.40%. That’s nearly half a point lower than just buying the Bund outright and yielding 0.08% (Bloomberg had a good article explaining the math if you are interested: https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2019-02-08/as-german-bund-yields-head-to-zero-they-still-beat-treasuries).

Consensus forecasts for US GDP are calling for a slowdown, probably to 2.0%-2.5%. Eurozone GDP and inflation forecasts are being lowered by half a point, down to about 1% and 1.5%, respectively. Japan’s next rate move is more likely to be a cut than a hike.

We might be spending a lot of time in 2019 talking about negative yields.

This Week

Some inflationary data, but Fed and ECB speakers will be the headline act. Powell speaks Tuesday.