Interest Rate Swap Overview

What Is a Swap?

A swap is a contract to exchange interest rate payments based on an agreed-upon notional schedule. The most common swap is floating to fixed swap, where a client pays a fixed rate and receives a floating rate, like LIBOR.

Generally, swaps are ideal for long term financings, usually five years or longer.

How Swaps Work

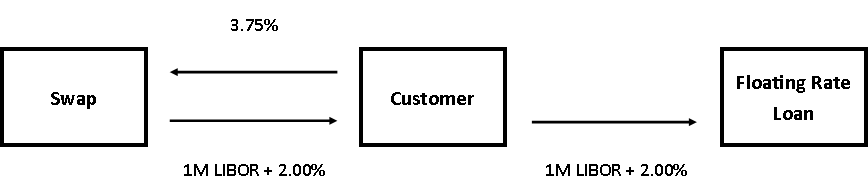

In this scenario, the borrower has a floating rate loan at 1mL + 2.00%. He swaps this floating payment out for a fixed rate of 3.75%.

Whether LIBOR goes to 0% or 20%, the borrower will always receive a floating payment on the swap that exactly offsets what he owes on the loan. The net effect is a fixed rate of 3.75%. Here’s an example using LIBOR at 0.25%:

Borrower Pays

Borrower Pays on Loan 0.25% + 2.00%

Borrower Pays Fixed on Swap + 3.75%

Borrower Pays 6.00%

Borrower Receives

Borrower Receives on Swap 0.25% + 2.00%

Borrower Receives 2.25%

Net Payment

Borrower pays 3.75% (6.00% – 2.25% = 3.75%)

How Swaps Work

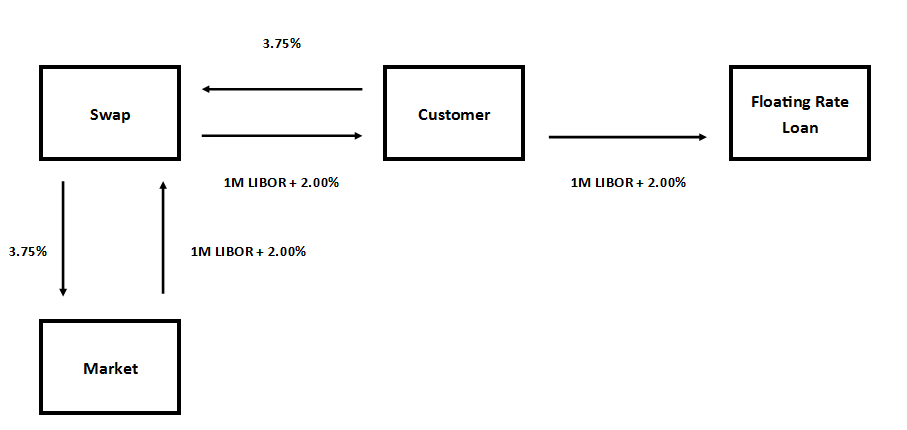

The bank lays the risk off in the market at the same time the customer locks in the rate over the phone. The swap marketer will usually say “let me put you on hold while I lock this in with the trader”. Unlike with a fixed rate loan, the bank now has no exposure to rising interest rates.

The “market” is really just other trading desks and no one is betting against the client. The desk simply quotes the rate available in the market and passes it along to the borrower.

But Wait, How Does the Bank Make Money in this Scenario?

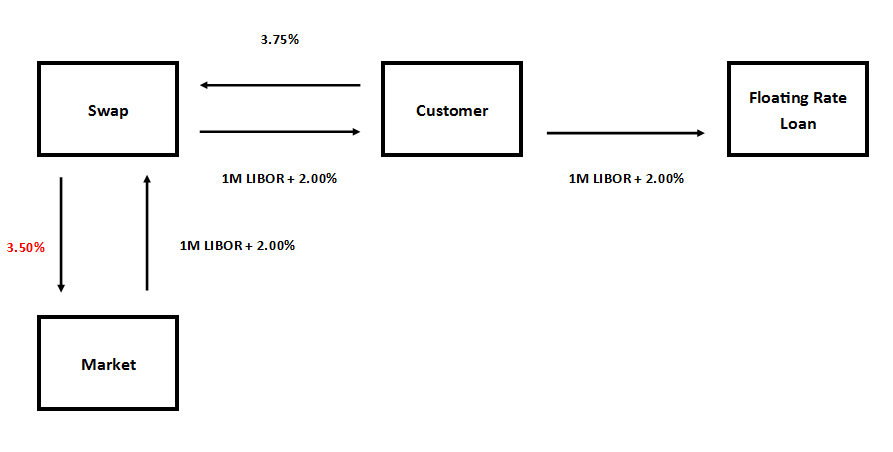

Because the rate the customer locks in is actually higher than the rate the trader could lock in at – notice the new rate below. The “market” offered 3.50% but the swap desk quoted 3.75% to the client.

This 0.25% of profit is per year, effectively increasing the customer’s borrowing spread from 2.00% to 2.25%. But the bank doesn’t earn this over time, it multiplies 0.25% per annum over the life of the deal and present values it back to day 1, capturing it as an upfront fee.

$100mm * 0.25% * 5 years = $1,250,000 additional fee income

The swap credit charge has the same impact as increasing the loan spread by the same amount.

The swap credit charge becomes an imbedded prepayment penalty carried forward.

Risks and Considerations

Frequently, the biggest risk on a swap is in the event of a prepayment. While it is true that swaps can be an asset if rates climb enough, this happens less frequently than expected. Here is the back of the envelope calculation for a swap breakage. For illustration purposes, we assume a 10 year swap initially that is prepaid after 7 years and rates have not moved at all since the time the swap was locked.

Average Remaining Notional * (Fixed Rate Locked – Replacement Rate) * Time Remaining

$100,000,000 * (3.75% – 2.85%) * 3 years = $2,700,000

If rates stay exactly the same, the swap will have a breakage of about $2,700,000 in seven years. Much of this is attributable to the effect of rolling down the yield curve. Three year rates are about 0.65% lower than ten year rates, so the swap naturally moves against the borrower over time. Add in the profit the bank makes at execution and the profit the bank will make at the termination, and it becomes easier to see why swaps are so rarely in the money to borrowers.

Other Considerations

- Additionally, swaps are commonly sold as being transferrable. Technically, this is true; however, from a practical standpoint it is very rare. The underlying real estate usually secures the swap exposure, so it is uncommon for a swap to be moved to other floating rate debt.

- The ISDA Agreement governs the swap contract. This is commonly described as being an industry standard, boilerplate document; however, they are highly negotiable and contain critical provisions that negatively impact the borrower in the event of a dispute.

- Dodd-Frank regulation has created a regulatory burden for borrowers looking to enter into a swap as well as annual renewal fees and processes.